This cafe, while unique, is not the only tribute to fecal matter in South Korea. Downstairs, vendors sell ddongbang, poop-shaped pastries stuffed with red bean paste and nuts to never-ending lines of tourists and locals. Nearby, toy stores display Kong Suni, a popular doll that “farts” and comes with a toilet, complete with flushable smiling dung.

In other parts of the country are mosaic poo sculptures, a toilet museum, Poopoo Land and even playgrounds devoted to Dongchimme, a poop-adorned character who enjoys sticking his fingers in others’ bums (the Korean equivalent of a wet willy.)

So the question remains — when, and more importantly why did poop become such a beloved icon here in South Korea?

Some believe dung’s idolization (particularly the image of the swirly mound type) stems from illustrations that were made famous circa the 1970s.

I, on the other hand, believe the roots of poo-poo’s popularity run much deeper and its notability reflects its importance in Korean history.

For one, golden-hued droppings have always been representative of wealth and good fortune. An old Korean superstition states that one will be prosperous if he or she dreams of poo; these days, it’s not uncommon for the superstitious types to load up on lottery tickets after having such dreams.

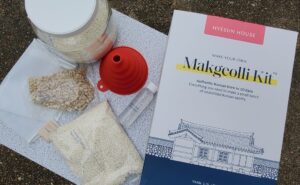

Feces also played an important role in traditional medicine. Animal and human excrement was used to concoct various remedies for ailments such as infections and broken bones. Many believed that the droppings of children, when fermented with rice to make ddongsul (“poo liquor”), were an infallible cure. Surprisingly, there are still a few practitioners throughout the country who continue to make this medicine, but the majority of younger Koreans are either unfamiliar with the concoction or are repulsed by the idea of it.

Park Wan-suh, a renowned Korean author, confirms my theory in her autobiography Who Ate Up All the Shinga?, in which she recollects stories about growing up in the Korean countryside during the Japanese occupation. In one chapter, Park focuses on her childhood memories of trips to outhouses with her friends.

She notes, “The most important thing was to deposit plentiful, well-formed turds in the outhouse. We knew there was nothing shameful in shit, because it went back to the earth, helping cucumbers and pumpkins grow in abundance and making watermelons and melons sweet. We got not only to savor the instinctive pleasure of excretion, but to feel pride in producing something valuable.”

Park clearly implies that poop wasn’t just the end result of a bodily function. It was fertilizer for food, a commodity that wasn’t necessarily guaranteed during those tougher times in a country with very limited natural resources.

Doggy Poo, an immensely popular children’s book and film, reiterates the importance of dung, but with a more meaningful plot.

After being brought into the world by a wandering puppy, Doggy Poo encounters a number of various animals and objects, and through his conversations with them, discovers what he really is — a stinky pile of crap. As the year passes, he contemplates his identity and purpose in life and at one point, even offers himself up as a meal for a group of passing chicks, only to be rejected by a disgusted Mama Hen. Although he struggles with his identity for some time, in the end, he realizes his potential as he helps a beautiful flower grow.

I watched the award-winning animated film in its entirety and have to say I was impressed with its inspirational themes: the cycle of life, realizing one’s role in the universe and the connection of all beings to the earth.

Yes, I realize I’m interpreting the symbolic themes of a claymation film about dog poop, but perhaps some of these are very valid reasons why the image of poop is so celebrated in contemporary Korean culture. And, though it pains me to say it, little Doggy Poo is cute. Heartbreakingly cute, in fact. Okay, there will be no more judgement of poo-lovers from my side anymore.

Whatever your opinion of poop may be, there’s no doubt that it has played an important role in Korean history and has developed into a beloved icon in today’s culture.

Please note that this post is meant to be a personal cultural observation, NOT an academic analysis, as I am not an expert on feces or its role in Korean culture. If you happen to be an authority on the subject and disagree with my opinions, please feel free to leave a rebuttal. (No pun intended.)

Words by Mimsie Ladner of Seoul Searching. Content may not be reproduced unless authorized.